A giraffe kissed me (when I was twelve) and I liked it.

It was a hot August day in Dublin Zoo, and the beautiful creature simply leaned over the fence and administered a big giraffy sloppy kiss to my face. I have never recovered from that action. It was the start of a long love affair with these graceful yet bad-assed critters.

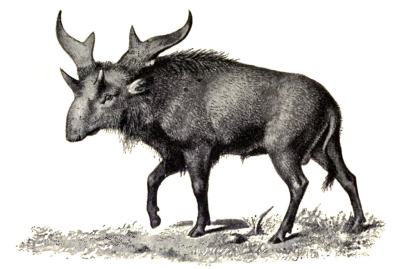

Our modern giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis, comes to us from the same ancient and elegant lineage as the genus Sivatherium. Remains of these beasts have been found in Africa but also in India, hence the name of Sivatherium – Shiva’s animal; the king of Indian deities as befits a creature with a literal crown of antler-like horns. They are believed to have only become extinct some 8,000 years or so ago, and it’s debated if the poignant rock art of the Sahara desert does indeed show species of Sivatherium, but more about that later. They were fantastical looking creatures; standing over 2 meters at the withers, with a full height of more than 3.5 meters, they were more powerfully built than modern giraffes. These wonderful animals had a short, broad skulls holding two pairs of horns: the front horns were fairly small, while the ones at the back were large, curved and palmate for shaking bushes for food as much as combat! We are used to the long, slender necks of modern G. camelopardis, but Sivatherium was having none of that! This was the ‘Rocky’ of the Giraffidae family. Strong, sturdy shoulders and a powerfully built bull-neck to hold up those ferocious antler structures (known to palaeontologists as ossicones), you would not intentionally mess with a Sivatherium of any species! One of the debates about Sivatherium’s feeding habits is whether it had the long tongue of modern giraffes, or if it relied on its teeth more. Certainly fossil remains show the teeth were more suited to mixed grazing, but the jury is still out.

A wonderful old school illustration of Sivatherium, recreated to be a little moose like. Note the wonderful ornament on it’s head. (Image from here).

The earliest humans in Africa would have witnessed herds of these truly awe-inspiring creatures grazing on a landscape that would change dramatically through to the Neolithic period. While it is likely prehistoric humans did hunt Sivatherium, their fate seems inextricably linked to the gargantuan and dramatic environmental changes of the Quaternary. The evolution of humanity too is linked to the conditions of Pleistocene Africa. The region we know as the Sahara has gone through fluctuations of climate, alternating between periods of aridity which have been relieved by wet periods which turned the dry landscape into green savannah. The earliest of these fluctuations have been linked to the evolution and diversification of hominids, but this is not the story of Lucy and her kin. This is the story of the Sivatherium.

Around about 9,000 years ago, the deserts of Africa were getting quite a soaking under climate conditions now known as the Neolithic Subpluvial. This was a time of plenty, where the desert bloomed, encouraging all sorts of creatures to live there, including wonderful African megafauna such as Sivatherium spp. Humans of course followed the herds of creatures, often with surprising results – in Nigeria there is an ancient petroglyph of a recognisable G. camelopardalis with a leash around its neck, possibly indicating a domestic scene, or the rope could be a lasso, in which case showing evidence of hunting.

Petroglyphs of giraffes with leash/lasso from the site of Dabous, north of Agadez, Niger. Image from here

With the Sahara and Sahel regions filled with wild creatures, fowl, lakes full of fish, it must have been a kind of Neolithic Garden of Eden ( complete with happy, colourful snakes too!) compared to the millennia previously when the Sahara was as dry and barren as it is today. Nothing, however, lasts forever. The climate shifted again, with the barren sands reclaiming the landscape gradually to form the conditions of the region which we know it for today.

There have been numerous studies performed on the bones of Sivatherium which all testify to a peculiarly high incidence of dental enamel hypoplasia. The teeth of the various species of Sivatherium were deficient in enamel, which was a problem for an animal that needed to consume tough vegetation, such as tree shoots, shrubs and more. It’s been considered that this indicates malnourishment from environmental stresses. Similar stresses have been noted on rhinoceros species during the Miocene climate changes in North America. As the preferred vegetation of Sivatherium withered and died from the encroaching desertification of their homelands, the babies would have suckled from their mums for too long. If mum wasn’t getting the nutrients she needed, the malnourishment spread to the little baby Giraffids. The end of the Neolithic Subpluvial meant the end of Sivatherium in Africa, as recently as the past 7 to 8 thousand years ago. They were not alone – it’s been estimated that at least 24 large African mammals of the Pleistocene vanished forever as the sands began their rulership of the African Holocene landscape.

While other parts of the globe suffered much greater megafaunal extinction through the Late Quaternary, there is a terrible sadness in that humans created a lasting record of the time when the Sahara was a place of life and beauty. Petroglyphs such as those at Tassili n’Ajjir, in Algeria, and Kuppenhole, in Tanganyika depict images of everyday life among Pleistocene wildlife. Sivatherium’s habitat changed, they could not adapt to the stresses of climate change combined with being hunted by humans so they passed into the stuff of legend.

Or did they? There is a strange and persistent palaeontology ‘urban legend’ which suggests the last of the creatures may not have died out until the end of the Sumerian Empire. A strange figurine found during archaeological excavations in the 1930s at Kish, Iraq, shows a creature with two sets of horns, a stocky elk-like neck and a giraffe-like face….Could the creature have survived as the regal pet of the Bronze Age Sumerian warlords? While it’s unlikely, it’s a fascinating idea – and the great thing about archaeology of course is that we can’t rule out that one of these days, more conclusive evidence just might be found to prove the creature made it out of Africa for another few thousand years!

Written by Rena Maguire (@JustRena)

Further Reading:

More on the Sivatherium ‘figurine’ by @TetZoo here.

Bedaso, ZK, Wynn, JG, Alemseged, Z, and Geraads, D 2013, ‘Dietary and paleoenvironmental reconstruction using stable isotopes of herbivore tooth enamel from middle Pliocene Dikika, Ethiopia: Implication for Australopithecus afarensis habitat and food resources’. Journal of Human Evolution. 64. pp.21-38. [Abstract only]

Colbert, E.H. 1936. ‘Was the Extinct Giraffe (Sivatherium) Known to the Early Sumerians?’ American Anthropologist New Series. 38.4. pp.605-608. [Abstract only]

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M, et al. 2014, ‘Study of the SHK Main Site faunal assemblage, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania: Implications for Bed II taphonomy, paleoecology, and hominin utilization of megafauna’, Quaternary International. pp.322-323. [Full article]

Faith, J.T 2014, ‘Late Pleistocene and Holocene mammal extinctions on continental Africa’, Earth-Science Reviews. 128. pp.105-121. [Abstract only]

Faith, J. T 2011, ‘Ungulate community richness, grazer extinctions, and human subsistence behavior in southern Africa’s Cape Floral Region’. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 306. pp.219-227. [Abstract only]

Franz-Odendaal, T Chinsamy, A and Lee-Thorp, J. 2013. ‘High prevalence of enamel hypoplasia in an early pliocene giraffid (Sivatherium hendeyi) from South Africa’ Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 24.1. pp.235-244. [Abstract only]

Franz-Odendaal, T. A., J. A. Lee-Thorp, and Chinsamy, A. 2002. ‘New evidence for the lack of C4 grassland expansions during the Early Pliocene at Langebaanweg, South Africa’. Paleobiology 28. pp.378–388. [Full article]

Geraads, D; Reed, K and Bobe, R.n 2013. ‘Pliocene Giraffidae (Mammalia) from the Hadar Formation of Hadar and Ledi-Geraru, Lower Awash, Ethiopia’. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33.2. pp.470. [Abstract only]

Mead, A. J. 1999. ‘Enamel hypoplasia in Miocene rhinoceroses (Teleoceras) from Nebraska: evidence of severe physiological stress’. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19. pp.391–397. [Full article]

Pachur, H and Hoelzmann, P 1991, ‘Paleoclimatic implications of late quaternary lacustrine sediments in Western Nubia, Sudan’, Quaternary Research, 36. pp.257-276. [Abstract only]

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 19/12/2014 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: June 24, 2016 | PLOS Paleo Community

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: June 24, 2016 | PLOS Blogs Network

I share the wish that there was good evidence of late survival of Sivatherium, but alas…

Research since Colbert’s note has been rather negative. (Colbert, b.t.w., was married to paleoartist Margaret Mathews Colbert: he published a charming autobiography, with a drawing of hers at the head of each chapter: one was of Sivatherium.) Basically, i.i.r.c., on closer examination the Mesopotamian statuette at issue looks a bit more deer like than Sivathere-like. I tried to resist, trying to pick wholes in the argument, but was in the end, alas, convinced.

I ought to give references, but it has been a while. Dartren Naish has discussed the problem (with references) more than once, I think, on “Tetrapod Zoology.” Key article is by Christine Janis … published in a crypto-zoology journal not held by many university libraries!

(Oh. The Colbert article in your references may only be an abstract, but I think it does include a picture of the statuette. Which I have looked at and dreamed…