I’ve wanted to see Dimetrodon ever since I was a little boy. My nose stuck in books about prehistoric animals, and there they were, these big scary creatures, with thick skulls and huge teeth, supporting that infamous sail on their back. They were even present in those packets of ‘dinosaur’ toys alongside pterodactyls and plesiosaurs. But Dimetrodon wasn’t a dinosaur. They scampered around on the Earth some 50 million years before the first dinosaurs even came to the scene. I knew this when I was that young, fairly round, blond-haired little boy. These animals were more closely related to us than they were to dinosaurs. And that has always fascinated me.

I saw Dimetrodon pop up in films. I remember sitting on the floor watching the old Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1959), on my own while my other siblings were running around outside, and there was Dimetrodon (well, not quite Dimetrodon, but an iguana with a sail strapped to it’s back, but back in the 80s, it was good enough for me!). I am not ashamed to say, I loved seeing Dimetrodon cause havoc in the underground tunnels more recently in Jurassic World: Dominion (2022). (Yes, I know, there probably weren’t even mosquitoes around 280 million years ago, but it is just a film, and it was awesome to see Dimetrodon!) It even makes an appearance in Fantasia (1940) where it is chased by a Tyrannosaurus rex!

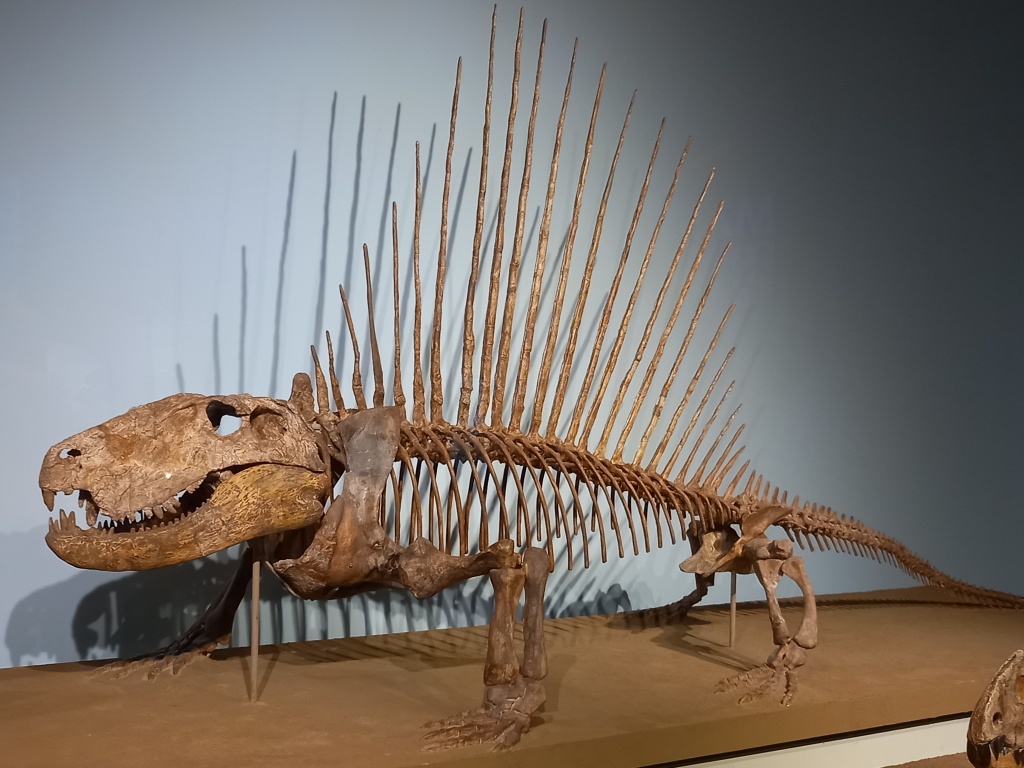

My childhood fascination was finally quenched. I finally saw it. A beautiful mounted skeleton on display at the Field Museum, Chicago. And it was beautiful. Those sprawling legs, reminiscent of a crocodile. Those incredible, long thin bones on it’s back where flaps of skin would have attached to form the sail, like nothing alive today. And that big, powerful, thick skull, housing those different shaped teeth. I was mesmerised. My partner patiently let me take it in. She didn’t rush me, didn’t tell me to hurry. She stood by my side, taking it in too. She understood. This was an important skeleton. A skeleton of one of our very early mammal relatives.

Mammals are familiar to all of us. They are all around us. Cats, dogs, sheep, giraffes, bears, mice, elephants, whales, the list goes on. They are us: we are mammals too. The mammals we know today are very different to that Dimetrodon skeleton proudly on display at the Field Museum.

Our readers know how incredible mammals are, because the majority of our posts so far are about mammals. Familiar mammals like sabretooth cats and giant sloths, and weird mammals like the odd Toxodon and those weird chalicotheres. Huge mammals like the enormous Zygolophodon or Deinotherium with those odd downward pointing tusks, and small mammals like the horny gopher or the venomous shrew. But why so many mammals? Why so many incredibly different types of mammals, and why did some just look plain odd? And how the hell does Dimentrodon fit into the picture? Well, it’s a story that began around 325 million years ago. A story that Steve Brusatte brilliantly tells us in his new book, The Rise and Reign of the Mammals.

There are so many books about dinosaurs that come out every year, and as for mammals, well, there maybe one or two about cats or dogs. It is refreshing to see an accessible, engaging read about mammals, and more interestingly, how mammals as we know them today came to be. It’s not a simple linear progression to those fur balls we recognise today: the cast of characters was vast, like a grand Tolstoy saga. The fossil record of mammals dating back some 320 million years is a complicated, busy bush. There were groups of mammals that were spectacular but left no ancestors, there were others that were almost a mammal but not quite a mammal, and others still that beggared belief: a myriad of characters in an epic tale of luck and survival. Brusatte’s narrative throughout is seamless. He elegantly weaves together the most up-to-date research from his colleagues around the world to give us the story of mammal origins. Which, don’t forget, is essentially, our very own origins too: it shows how we are so closely linked to the rest of the animal kingdom.

It is such a fascinating history. Millions of years, across continents, and enigmatic fossils shedding light on a truly remarkable world long forgotten. There are things outside an animal’s control that have a lot to play on their evolution. And this is just one of the great things about Brusatte’s writing. He includes all the most recent research, not just the fossils themselves, but the continents, the climate, and other animals that shared the scene with early mammals, many of which were competitors. As climate changed, so did the vegetation, which in turn changed the way some mammals fed, some adapted well, others didn’t, resulting in whole groups of mammals disappearing forever. There’s also an incredible amount of luck: being in the right place at the right time; having the right little features to help them through a tough time. It’s fascinating to know that a single event (albeit an enormous extinction level event) some 66 million years ago cleared the way for mammals to roam freely, and expand into new niches and evolve into the most incredible range of shapes and sizes.

One of the (many) things I really liked in this book were the personal stories from his own fieldwork and experiences. It makes the book relevant, talking about real people making real discoveries (and not just old white dudes, but palaeontologists from all backgrounds, all over the world, studying early mammals and their ancestors). One moment you will be reading about dinosaur-eating mammals, the next you are whisked off to the Isle of Skye in Scotland. You almost get a sense of being there with Brusatte and teams of palaeontologists in the field. It a nice touch that flows perfectly with Brusatte’s narrative, and allows your brain to take a small break from some difficult terms, which he summarises again later for readers. I have read scientific papers about early mammals and their ancestors, and I can tell you, they are not the easiest of things to digest. Brusatte, however, writes so engagingly, you hardly even notice you are learning new terms, or names of long-vanished lineages. It’s obvious that he is very conscious of the reader, and that many people would be unaccustomed to many scientific terms, but he explains them clearly, and again later, as he wants us to make sure that we don’t get lost. Brusatte wants readers to enjoy this fascinating tale that took place over hundreds of millions of years.

And what about Dimetrodon? Our familiar scaly, sailed beast comes in fairly early in the story of mammals. Around 325 million years ago, there were small scaly animals, and they split into two groups: one that would eventually give rise to reptiles (diapsids), and the other group were the ancestors of all mammals alive today (synapsids). The group that gave rise to mammals evolved separately from the reptile group, evolving their own unique features. And this is the key – those features that we know as mammalian, like three ear bones, hair, secreting milk, did not all arise at once. Some features appeared and they were an advantage to those animals, and their descents would evolve more mammalian features. Dimetrodon was one of these animals. The world was changing 300 million years ago, with the damp coal forests shrinking, making way for drier land: a land better suited for animals that didn’t need water to lay their eggs. Enter Dimetrodon, which evolved from the synapsid (mammal) group of those scaly little critters. What’s amazing in Dimetrodon is the teeth. Reptile teeth are all the same shape, in mammals we have different teeth at the front, middle and back of our mouths. We all know we have incisors, canines, premolars and molars, and if you peer into the mouth of Dimetordon, you will see teeth that are pretty similar to ours, not reptilian, but teeth of different shapes and sizes: big canines, and different shaped teeth at the back compared to the front. And Dimetrodon wasn’t the only early synapsid around. There were other closely related beasts, like the chunky Bradysaurus, or those terrifying sabretooth killers, the gorgonopsids.

This is, of course, only a snap-shot of the full story, which Brusatte describes with much more elegance than I. He describes such an huge range of creatures from incredible fossil discoveries, and how each feature that makes a mammal a mammal came to be over millions of years. But it doesn’t feel like you are reading a book full of facts, Brusatte vividly conjures up these ancient places where life, and the Earth itself, would have been very different. You get a glimpse into the past, 280 million years ago to when Dimetrodon and other incredible beasts were roaming the planet, or 40 million years ago where you are watching a tropical rainforest full of strangely familiar creatures. You can almost feel the heat, the moisture, and smell the air, from millions of years ago. Looking at mammals today, these prehistoric relatives look more like something from a fantasy than anything related to us.

You and I are today because of an uncountable myriad of chance happenings. A group of animals with hair, that fed their young milk, and had a mouthful of different shaped teeth, were lucky enough to survive. Evolution doesn’t lead to greatness. Animals alive today are not ‘better’ than animals 280 million years ago. Those animals back then were perfectly adapted to their environment. Dimetrodon and it’s kin, may look odd, ‘primitive’, but these were the top beasts of the time, and those teeth gave them an edge over other animals.

The evolution of mammals, of what we know as mammals today, took place over 325 million years. They didn’t just appear, but slowly features evolved, and these features and adaptations helped animals survive. This book is one of the finest, most accessible, I have read about the origins and evolution of mammals, and it’s one I will read again, if only to be transported back to a time when such incredible beasts walked the Earth. Incredible beasts, and extraordinary ancient relatives. We are here today because of creatures like Dimetrodon, the great-grandparents of us.

Written by Jan Freedman (@JanFreedman)

Further reading:

Brusatte, S. 2022. The Rise and Reign of the Mammals. Picador. [Book]

We use the word HUMANS all the time, perhaps if we said MAMMALS instead, maybe we would better understand our connections with all the forms of life on earth. Thank you for this very full and informative post! 🙋♂️

I just (last week) read Brusatte’s book. I enjoyed it, as I expected I would (I have a long-standing interest in mammalian evolution, and a collection of Dimetrodon toys and figurines covering most o a shel of one bookcase!).

How does it compare to others? I’d say it is intermediate between Elsa Pancirolli’s “Beasts Before Us” and more technical works like Kemp’s book (to which Brusatte refers repeatedly): more fact heavy than Pancirolli, more personal (in, e.g., the stories about field work that Jan motions) than Kemp. I think I’d recommend Pancirolli’s book to someone of not particularly scientific tastes who wants a hint at what makes palaeontology interesting, and Brusatte’s if they get hooked and come back for more… Or alternatively, Brusatte for someone wanting to start studying mammal history, with Pancirolli as complementary.

(The two authors both have Scottish connections, and know each other.)

One thing I thought was particularly valuable in Brusatte’s book was the extensive set of references at the back: not just a bibliographical list, but a bibliographical essay pointing out the works related to specific topics: someone with access to a university library or other “portal” to electronic copies of technical journals could use Brusatte’s notes as a guide to a course of reading of the original sources.

—

One thing I wasn’t sure of: the reference to “scaly critters” at the beginning, referring to the common ancestors of Synapsid (mammal line) and Sauropsid (=reptiles and dinosaurs) animals. There are many different integumentary features called “scales,” and some of them are not plausible for basal amniotes. The sort of scales we associate with lizard skin, for example, are a much later evolutionary development.

I’m reading this book at the moment, Jan. Thanks for the review, and your personal angle on it through Dimetrodon. I’d note, though, that Bradysaurus is not a synapsid, but a parieasaurid parareptile.

Oh, dear! You’r right, Don: the absence of the “trade-mark” synapsid opening behind the eye orbit should have been a tip-off! … But with the bulky body and small head, maybe it is just filling in for some Caseid pelycosaur: a genuine mammal-relative with an “architecture,” and maybe a lifestyle, similar to Bradysaurus?

—

(B.t.w.: in case I didn’t make it clear enough in my post, I very much like BOTH Steve Brusatte’s book and Elsa Panciroli’s. They cover, in sense, the same ground — mammal history from the beginning of the Synapsids to the climate-change-threatened future — but in very different ways.)

I just requested this book from my library and i am looking forward to reading it. Thanks for the rec!