In the frozen desolate lands of north eastern Russia, there is a unique mammoth graveyard. This graveyard is different than other fossil sites in the world. After being exposed for the first time in tens of thousands of years, the bodies are fresh: flesh is soft, the stench of death is overwhelming. Instead of the dead entombed in rock, they are trapped in frozen soil. When this soil starts to melt, it is mushy, sticky, messy. A little like a chocolate cake.

Frozen remains have been found across Siberia for centuries. Carcasses were so fresh that in the late 1700s they were thought to be giant underground rats: these behemoths used their enormous tusks to dig huge tunnels underground. They fed from the Earth. They also knew when they were going to die, for they dug out of the ground to die on the surface, which is why they are found half sticking out of the ground. It’s quite a marvellous idea, but sadly these were not giant underground rats. They were mammoths.

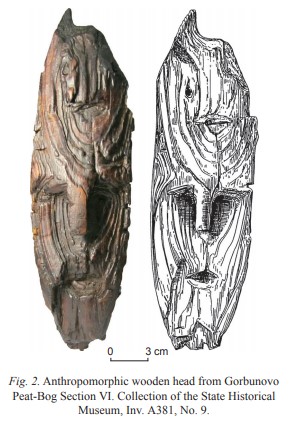

The Adams Mammoth, illustrated in the early 1800s before it was fully excavated. The trunk of this mammoth was scavenged and missing from the specimen. The pointing back tusks may be a nod to those giant underground rats. (Image Public Domain. From here)

Over the years hundreds of thousands of mammoths travelled in great herds across Siberia. Herds moving back and forth, following the seasonal changes, following the food. Many died on this journey. This harsh environment claimed the young as well as the old. The dead may stay dead, but they can speak of their time on Earth.

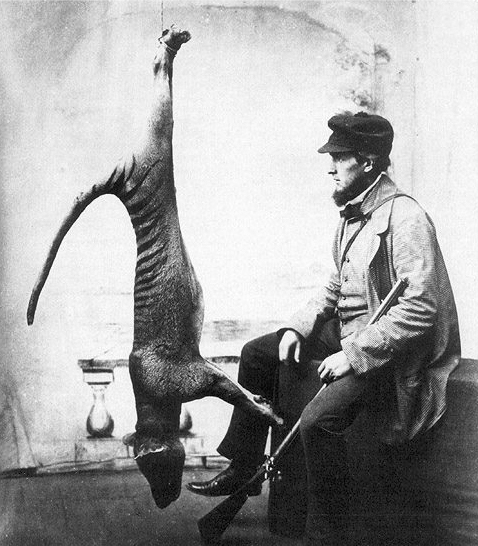

The most complete frozen mammoth, and arguably one of the most beautiful, was found relatively recently. She was small and exceptionally persevered. A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to see her on display at the Natural History Museum, London. Only once have I ever seen anything more beautiful.

About as long as my arm, she was almost perfect. Her small trunk curved down and in. The ear was nothing like the modern elephant’s: it was tiny. She wasn’t covered in fur like I expected, this had been lost, but there were two small patches of fur, giving a glimpse of the colour of this little mammoth. She was inches away from my face. Secure behind thick glass, positioned carefully in an environmentally controlled case, she sat silently as I, and hundreds of other visitors, looked at her with awe.

Her name is Lyuba. She is a very young woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). And she is a thing of rare beauty.

The beautiful baby mammoth, Lyuba. (Image Matt Howry. From here)

Today Lyuba is in the collections at the Shemsnovskiy Museum and Exhibition Centre. But she almost never made it to the public eye.

Astonishingly, she was discovered separately three times. Firstly she was seen in September 2006 by a reindeer herder Niklola Serotetto, but he didn’t report the find. The following year in May 2007, another Nenets reindeer breeder and hunter, Yuri Khudi, and his sons came across the small mammoth. Khudi travelled across land to find a friend to speak to about the discovery. When he returned, Lyuba wasn’t there. She was discovered by a third reindeer hunter and moved to the nearby village of Novyy Port. Here Lyuba was placed outside a shop, where dogs had chewed off an ear and most of her tail. She was reclaimed by Khudi, who made arrangements for her to go to the Shemsnovsdkiy Museum and Exhibition Centre.

In honour of her discoverer, and his tenacity at making sure this frozen mammoth was safe for future generations, she was named after Khudi’s wife: Lyuba. Which also means love. Perhaps there is no better name for this animal.

Despite being 41,000 years old, we have found out a surprising amount of information about Lyuba.

She was found lying on top of ice by the side of a river. This is pretty unusual for frozen specimens in Siberia: normally they are found half exposed, with other bits of them still frozen in the ground. Some carcasses are fully exposed, as the ice melts in the summer months, but these are partly eaten by scavengers. Lyuba was perfect, which was a bit of a mystery. After visiting the site, mammoth palaeontologist Dan Fisher along with a few colleagues soon discovered how she became to be lying there. During the warmer months, ice alongside the river melts and sometimes large chunks break off and float downstream. It is likely that Lyuba, possibly still enclosed by some ice, broke off and floated down the river. Luckily, she didn’t float too far, or stay in the water for too long. She became grounded at the side of the river, lying in silence with the high pitched whistle of the wind blowing over her.

She is the best preserved mammoth in the world. Missing an ear and parts of her tail from being chewed off by dogs, and missing her toenails, she is externally near complete. Only a few small patches of fur remain, showing she was (probably) light brown-orange colour when she was alive. A recent study shows that her internal tissues were incredibly well preserved. Strangely, these were very acidic whilst the collagen structures (like bone and cartilage) were broken down. This suggested that lactic-acid bacteria had colonised her body, preserving the internal organs perfectly, in a similar way to how museums preserve specimens in formaldehyde.

A CT scan of Lyuba, showing the incredible details of her insides. (Image Ford Motors, for the International Mammoth Committee)

With this incredible preservation of her insides, we have found out a lot about her short life. Some of her mother’s milk was found in her stomach, showing that she fed soon before she died. Scientists also found some mammoth dung in her intestines. This isn’t as strange as it sounds. Elephants today may eat their own dung, especially during tough times. For young calves, this is a good way of developing their digestive system ready for eating the tougher vegetation that they must when they wean off their mother’s milk.

Lyuba was small. And she was still getting milk from her mother. But do we know how old she was when she died? Incredibly, we do. Detailed studies of her teeth which looked at the neonatal growth lines, indicated she was only 30-35 days old when she died. Looking at the chemical isotopes in her teeth (which can provide clues to what vegetation was growing around the time of her death), we even know that she was born in the early spring.

Her body shows that she didn’t die of any broken bones and was a very healthy calf. Because her organs have been so well preserved, we know how she most likely died. Detailed CT scans show her oesophagus and trachea were all filled with mud, suggesting she suffocated. We would know more if she was found in the original place where she died, as the surrounding area would give more information. Based on what evidence there is, it appears Lyuba got stuck in mud at the side of a river. Her little body didn’t have enough power or strength to pull herself out, and she slowly sunk into the mud and suffocated.

Did mammoths mourn for their dead? Elephants have been seen to push a dead relative with their trunk and feet, and stay by their side for days. Both African and Asian elephants have been shown to carry out this behaviour: an awareness of their dead. Modern African and Asian elephants split around 7 million years ago, and the first mammoths split away from Asian elephants around 5 million years ago. It is very likely that they shared this behaviour.

It is not difficult to think of Lyuba’s mother, with her herd nearby, standing close to the river near the spot where she died. Perhaps trumpeting. Perhaps tentatively moving closer and then stepping back with those huge feet. For a day. Or maybe for a few days. Before the cold, icy Siberian winds blew through their thick fur, pushing them onwards.

Written by Jan Freedman (@JanFreedman)

Further reading:

Find out more about woolly mammoths in our post about them here.

We wrote about another find in Siberia, which lead to possible cloning hopes.

Discover all ten different species of mammoths in our post here.

Barnes,, I. B. et al. 2007. ‘Genetic structure and extinction of the woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius.’ Current Biology. 17:1. pp.1072-1075. [Full article]

Fisher, D. et al. 2012. ‘Anatomy, death, and preservation of a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) calf, Yamal Peninsula, northwest Siberia.’ Quaternary International. 255. pp. 94–105. [Full article]

Fisher, D., et al. 2014. ‘X-ray computed tomography of two mammoth calf mummies.’ Journal of Paleontology. 88 (4). pp.664–675. [Abstract only]

Kosintsev, P, et al. 2012. ‘Environmental reconstruction inferred from the intestinal contents of the Yamal baby mammoth Lyuba (Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1799).’ Quaternary International. 255. pp.231–238. [Full article]

Lazarev, P., Grigoriev, S., & Plotnikov, V. 2010. ‘Mammoth calves from the permafros of Yakutia. Quaternaire. Hors-Serie. 3. pp.56-57.

van Geel, B, et al. 2011. ‘Palaeo-environmental and dietary analysis of intestinal contents of a mammoth calf (Yamal Peninsula, northwest Siberia).’ Quaternary Science Reviews. 30(27-28). pp.3935–3946. [Abstract only]