ALERT, THIS BLOG IS NOT SUITABLE FOR VERY LITTLE KIDS, AND PROBABLY IS RATED AROUND A PG12!

There’s been a huge buzz about the early Mesolithic dates of the Shigir wooden figure, from Ural Russia, and it isn’t too often we can incorporate human activity into the Pleistocene in such a very direct way! This blog is a little step to the side for us, as we get to take you on a pretty wild and wacky journey from 9600 BC through to only 2000 years ago!

There are stories from the deep past we won’t ever hear with our ears, but that’s not to say we cannot hear them. Archaeology tells those stories, the ones that I think matter. The past I’m talking of is the one wrapped in skins and furs against the spiteful cold of the Younger Dryas. It has wise eyes and a hopeful heart; it knows what sustenance may still grow in snow and biting cold, and knows where the animals go to drink deep in parched summers. That past is carried in each and all of us, we are here because our ancestors survived the ice and cold with wisdom, courage and plain stubbornness. There’s times, however, something is found in bog, field or lake which beckons us to gather round in a circle, sit down, put the phone on silent, and listen to the past intently.

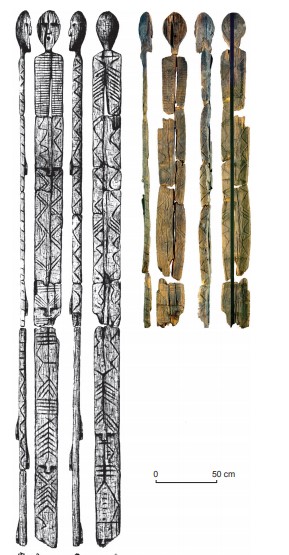

The Shigir wooden idol is one such object. It is an enigmatic wooden figure which, I admit, I could spend days just looking at, and ‘listening’ to, for it must have such a story to tell of the people who made it. It was found in a peat bog (all the best things are, imo) 100km north of Yekaterinburg, Russia, at the end of the 19th century. It stands head and shoulders (literally) above other objects of the past as it would have measured around 5 m when complete, a tower of song, stories and memory set down some 11000 years ago. It is made of larch wood, and decorated with deep zig-zag lines on the torso, with 8 intriguing smaller faces carved as part of the design of the body. All the faces are unique and expressively stern.

The Shigir figure, from N.M. Chairkina , 2014, p85. Look at the little faces all along the body!

It’s likely that the cosmologies and foundation myths of these ancient, clever people intertwined with memory of group effort, celebrating those who made it through the ice. Think how delicious it is that when you look at these images on pixels made of light and colour on your computer, you may well be looking at remembered faces of tribal leaders, or of ancestors.

Is he Groot? A face from the deep past;one of the Gorbunovo wooden figures, from Chairkina, 2014.

Pollen samples taken from the Shigir peat bog show the presence of tall trees such as larch and pine through the last days of the Younger Dryas and the start of the Pre Boreal phase (11kya to 9.8kya BP), allowing some reconstruction of the site, showing that sometime around 9600 BC (cal.), someone, or a group of someone’s, made this massive and meaningful figure, as guardian or statement. There are others of this time, too; Shigir bog may have produced other figures, while the Gorbunovo bog , also in the Urals, has an entire collection of wooden ‘people’, ranging in dates between the late 4th–early 2nd millenniums BC, firmly during the Eurasian ages of metal. There are also notable and wonderfully vital animal carvings; horses, deer and bison represented with flair and understanding.

The Red Man of Kilbeg, Ireland. From Stanley 2006

These Eurasian people were highly mobile hunter gatherers, following herds and living in balance with their environment. They say that this lifestyle allows more time for observation and understanding of the environment. This wisdom perhaps was cast aside to some extent during the Neolithic agricultural expansion, when humans were tamed by the crops they grew, to live in one settled place. We are not likely to know exact details of what beliefs were held. We might catch glimpses of it, though, through objects of the past, like the Star Carr stag tine head-dress, or the Sorcerer of the Cave of the Trois-Frères in France. Equally, we might catch reflections of it in surviving indigenous cultures, such as the Ugrian people of Eurasia.

The Shigir idol is the first known example of wooden ‘idol’ figures, which enjoyed a remarkable longevity of use and meaning (whatever the meaning actually was). Somehow, they travelled westwards over time, along with metal use and horses and domesticated animals as a whole. They are found all over western Europe, often associated with toghers and trackways, the wooden paths across wetlands and bogs, suggesting they held some sort of guardian status for travellers.

The cheeky little grinning oak man from Houten, Willemstad, in the Netherlands, dates to the junction of the Mesolithic and Neolithic, around 6400 BC and seems to be the earliest in western Europe. A serene dryad found in Pohjankuru , Finland, dates to around 3000 BC, with only the head having survived to the modern day. The ash wood ‘God dolly’ found on a wooden track across the Bell Track in Somerset, England, is the (so far) earliest of the British Isles figures, dating between 2285 and 3340 BC (cal.). It’s a particularly interesting one, as despite the diminutive size, both breasts and phallus appear to be carved into it – it is the first obvious display of a recurring theme of emphasising genitalia on these later wooden figures.

The Dagenham figure, from the London of 2250 BC (cal.), is made of Scots Pine, and has a bored hole in the pubic area, where an inserted peg could change it from being female to male. The stern faced yew-tree Ralaghan figure (cal. 1200 BC) from a good County Cavan peat bog, shares this ambivalent sexual identity, whereas the oak Lagore figure (cal. 2274 BC), from the famous County Meath crannog, is void of facial features, but has a noticeable phallus. My favourites, and the most amusing to the modern eye, are the collection of small figures, around 30cm in height, found at Roos Carr, northern England. Made of pine, and dating between 770-400 BC, these little figures have quartz pebble eyes, stand in a snake-shaped boat and came with a little wooden box of detachable pegs which could be inserted into the bored holes in their pubic areas, and their little shields hung on top of those pegs! It’s a bad reflection of the 21st century that all I can think of nowadays with these chaps is Lonely Island’s eminently NSFW video, Dick in a box. I was even caught by a curator singing it to the figures in the Hull & East Riding Museum (sorry again for that, lads!), because that’s the kind of behaviour you expect from this member of Twilight Beasts!

Two of the Roos Carr figures. Worst boy band ever….?

Equally amusing for his lop sided grin is the Danish Broddenbjerg Idol, one of the later figures, belonging to the Pre-Roman era of the Iron Age. His phallus is made of a large protruding branch, which resembles other sexualised idols from the Braak Bog, in Schleswig Holstein, which also date to the 5th century BC. The craftspeople incorporated the natural shape of the wood to include sexual features within the figures. Faces are occasionally depicted on these Bronze and Iron Age specimens, but is not the primary focus of the objects. They can be male, female, and sometimes both, but they lack the human faces like those of the Mesolithic Shigir figure.

Broddenbjerg figure, optimistically male, found near Viborg Denmark. On display at Danish National Museum, Copenhagen. Photo by Stephano Bolgnini Wikicommons Media Commons Licence.

We can suspect the western European figures are guardians of wetlands and soggy dangerous places, as so many have been found along trackways. Bogs and marshes are what archaeologists call liminal places, in that they are neither solid land nor bodies of water – just think of how Tolkien showed the Dead Marshes as places where life and death got a bit smudgy under the brackish water! Imagine dusk falling, and walking home across a bog trackway, sometime in the Bronze Age; the only noise is the wind soughing in the sedge, and the odd gurgle and plop of ‘something; in the water. They say that when darkness falls, strange lights flicker across the bog, which could lead you to your doom in the rusty-coloured waters – you don’t know yet that it’s methane from decaying vegetation. You just know danger is everywhere. You’d want as much protection as you can get from supernatural beings, to get you home.

All fine and dandy – but why does the ‘protection’ of these figures last from the Younger Dryas, 11000 years ago, right through to the expansion of the Roman Empire across western Europe? Do the later European ones mean the same as the Shigir idols? Does the symbolism even stay the same over those 9000 years? Certainly, the sexual display aspect seems to be an addition of the Neolithic period , as the early Eurasian ones do not appear to exaggerate any genitals. Could it be that the wooden figures , from the Neolithic onwards, tried to harness the wild and ancient spirits of the primeval, uncontrolled, un-humanised forests of the Mesolithic? After all, the hunter-gatherers of Shigir would have lived daily with the rawest expressions of nature, with little prudery. The primeval forests of the Mesolithic were part of a landscape which was important to life, providing food and wood for temporary shelters. Only with the concepts of land ownership – and human ownership – in the Neolithic, would deep forests become viewed as utterly fearful places, an arena where human control carried no power.

Could this be why the wooden idols were shown with very obvious genitalia, to represent the part of the human experience which often remains wild at heart, to match the wildness of uncontrolled nature in the Mesolithic?

There’s a fascinating remnant myth from Ireland of the ancestral demi-goddess Tailtu. According to the Lebor Gabála (Book of Invasions), Tailtu was a bit of a Paul Bunyan, several millennia early, as she single-handledly cleared the great ancient forests from Ireland, to allow agriculture to commence for new arrivals to the island. She collapsed, dead, on the hill which now bears her name (Teltown, in County Meath, an area with a wealth of archaeology and legend). She is, therefore, a de-wilding goddess, perhaps illustrating the discomfort of protohistoric peoples with deep, dark forests and trees with gnarled shapes which represented all the things a cattle and sheep farmer really didn’t want around, marking the difference between settled, farming societies and the ancient hunter gatherer societies.

There is also the aspect of the woods the figures are made of. There’s magic in wood; you knock on it, to wake up the tree spirit, remember, even in the 21st century! Alder bleeds a red sap, making figures look bloodied. It is a wood which has been used for shield making during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages as well – it bleeds, so you don’t have to. The Kilbeg wooden figure of the Irish Bronze Age (which looks like a slightly animated spine; quite creepy) would have looked quite frightening when fresh, just as the Scottish Ballachulish female figure would have. To the best of my knowledge, there has been no examination of the Mesolithic wood figures to assess the choice of woods for manufacture, or whether it was a case of using whatever was growing. This was the end of the Younger Dryas, and the start of the Pre-Boreal climate phase, when suddenly the land woke from deep freeze, and the open tundra land was colonised by the first post-glaciation trees. Could the towering nature of the Shigir idol reflect the joy of the Mesolithic people at the tall trees now growing, and the faces represent memories of the wise old ones who got the group through the last cold snap of the Pleistocene.

UCD experimental archaeology displaying Bronze Age-style alder-wood figures, carved with bronze axes by UCC ‘s Pallasboy project staff, Ben Gearey, Orla Peach-Power and Mark Griffiths )https://thepallasboyvessel.wordpress.com/) December 2016 . Photo by @UCDArchaeology Experimental Archaeology

The Shigir figure, then, may well be a tribal identity symbol, carrying a very different meaning than the later figures. These later figures appear to have chosen to adopt the guardian qualities of the ancient Mesolithic specimens, but not the incorporation of ancestors into their decoration. Why would you want your farming ancestor’s face in a maenad-ish wood sprite who was likely in cahoots with hunter-gatherers? You may well have wanted the sexy fertility of the wood spirits, and their protection, but placing them in liminal spaces, like toghers on bogs, meant that they weren’t too close to tamed, settled humans, but they still received respect due as ancient things, ensuring that they’d be happy enough in a wild, and uncontrolled place, happy enough perhaps to offer protection….

From Coles 1990, a diagram showing a togher, or trackway, across a bog in Lower Saxony, with two wooden ‘idols’ either side.

We won’t ever know for sure. This is purely supposition based on the stuff that we do know. What we can say is that the longevity of use of these bog idols is remarkable, regardless of how much of their original meaning they kept ( or didn’t) as they moved west across Europe. Trees are iconic things, even into the 21st century, and Marvel’s Guardian of the Galaxy ( and I’m sure of wetlands too!) of Groot – and even he has developed a bit of an attitude in the most recent movies, although certainly not half as wild and uninhibited as the bog idols! These ancient figures do, however, show the complex relationship of humanity with their environment from the Pleistocene onwards, and how trees were as vital to humans, both physically and spiritually, as the megafauna of the past.

Written by Rena Maguire (@JustRena)

A boggy bibliography!

Bond, C. 2010. ‘The God Dolly wooden figurine from the Somerset Levels, Britain: the context, the place and its meaning.’ In D. Gheorghiu and A. Cyphers (eds) Anthropomorphic and Zoomorphic Miniature Figures in Eurasia, Africa and Meso-America. Oxford: Archaeopress/BAR International Series 2138. pp 43-54. [Full Text]

Berbesque, J.C., Marlowe, F.W., Shaw, P. and Thompson, P., 2014. ‘Hunter–gatherers have less famine than agriculturalists’. Biology letters 10. 1. [Full Text]

Brunning, R., Hogan, D., Jones, J., Jones, M., Maltby, E., Robinson, M. and Straker, V., 2000. ‘Saving the Sweet Track: The in situ preservation of a Neolithic wooden trackway, Somerset, UK’. Conservation and management of archaeological sites. 4. 1. pp.3-20. [Abstract]

Chadbourne, K., 1994, January. Giant women and flying machines. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. 14. pp106-114 [Full Text]

Chairkina, N.M. 2014. ‘Anthropomorphic Wooden Figures from the Trans-urals’. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 42. 1. pp.81-89. [Full Text]

Coles, B. 1990. ‘Anthropomorphic Wooden Figures from Britain and Ireland’. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 56. pp. 315-333. [Abstract]

Conneller, C. 2004. ‘Becoming deer. Corporeal transformations at Star Carr’. Archaeological dialogues. 11. 1. Pp 37-56. [Full Text]

Dimbleby, G.W., 2017. The domestication and exploitation of plants and animals. London: Routledge.

Green, M.A., 2004. An archaeology of images: iconology and cosmology in Iron Age and Roman Europe. London: Routledge.

Hukantaival, S. 2009. ‘ Horse skulls and ‘alder horses’: the horse as depositional sacrifices in buildings’ in Bliujiene, A ( ed) Archaeologia Baltica 11: The Horse and Man in European Antiquity, 350–357. Klaipeda: Lithuanian Institute of History Press. [Full Text]

Irsenas, M. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic Stone Ave art in Lithuania, and its archaeological context. Baltica 13. [Full Text]

Maguire, R. 2014. ‘The Y-piece: Function, Production, Typology and Possible Origins’ Emania. 22. pp 77 -99.

Molloy, B., 2009. ‘For Gods or men? A reappraisal of the function of European Bronze Age shields.’ Antiquity. 83. 332. pp.1052-1064. [Abstract]

O’Sullivan, A., 1990. Wood in archaeology. Archaeology Ireland. 4. 2. pp.69-73.

Ozheredov, Y.I., Ozheredova, A.Y. and Kirpotin, S.N., 2015. ‘Selkup idols made of tree trunks and found on the Tym River’. International Journal of Environmental Studies 72. 3. pp.567-579. [Abstract]

Potemkina, T.M. 2014. ‘Sanctuary of Eneolithic and Bronze Age in Western Siberia as a source of astronomical knowledge and cosmological ideas in antiquity’. Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 2. 1. pp.50-89. [Full Text]

Raftery, B. 1987. ‘Ancient Trackways in Corlea Bog, Co. Longford’. Archaeology Ireland. 1. 2. pp.60-64. [Full Text]

Smirnova, O.V., Kalyakin, V.N., Turubanova, S.A., Bobrovsky, M.V. and Khanina, L.G. 2017. ‘Development of the European Russian Forests in the Holocene’. European Russian Forests pp. 515-536. [Abstract]

Stanley, M., 2012. ‘The red man of war and death? ‘Archaeology Ireland. 26. 2. pp.34-37.

Stanley, M. 2006 ‘The Red Man of Kilbeg: An Early Bronze Age idol from County Offaly’ PAST 52. pp 5–7. [Full Text]

Taylor, T., 1996. The prehistory of sex: four million years of human sexual culture. London: Bantam.

Zhilin, M., Savchenko, S., Hansen, S., Heussner, K.U. and Terberger, T., 2018. ‘Early art in the Urals: new research on the wooden sculpture from Shigir’. Antiquity. 92. 362 [Full Text]

Also, worth checking online, https://thepallasboyvessel.wordpress.com

and https://www.facebook.com/groups/UCDExperimentalArchaeology/

Pingback: Pagan Idols of the Mesolithic | Letter from Hardscrabble Creek

You wrote: “Certainly, the sexual display aspect seems to be an addition of the Neolithic period , as the early Eurasian ones do not appear to exaggerate any genitals. Could it be that the wooden figures , from the Neolithic onwards, tried to harness the wild and ancient spirits of the primeval, uncontrolled, un-humanised forests of the Mesolithic? After all, the hunter-gatherers of Shigir would have lived daily with the rawest expressions of nature, with little prudery.”

Yes “prudes” were horny and in denial…

???

not sure what yer getting at.

But the art is lovely.

Hi Tabby. I wrote this as an archaeologist, and not a palaeontologist, so will try to explain to you. Perhaps because the Mesolithic lived their lives within an arena of’wildness’, ie, fully integrated with their environment, the need of fertility imagery was not necessary – after all, the pre-Boreal stage was causing vegetation to return rapidly after the Younger Dryas. They lived with wildness. However, the Neolithic period meant that wildness was to be feared – large hairy animals lurked in forests and wanted to eat the livestock so carefully curated by new farmers. We know from the landscapes of Stonehenge etc, that boundaries between wilderness and cultivation were very important. Once you passed your farmland, here be dragons ( and wolves, ghostly ancestors and general scary things!). Fertility, controlled fertility , was very important indeed.So,none of these people were prudes, or in denial, but sexuality, and the uncontrolled, were seen in different ways by ancient peoples. Maybe the Mesolithic took it all for granted,but the Neolithic and subsequent periods certainly didn’t. I hope that answers your questions to some extent.

OH! you should put that directly into your article… that’s really helpful. I appreciate you taking time to explain. I am ever refreshed by your work(s). You help me understand and explore deeper. Thank you.

I don’t mean you “should” do anything… I just mean that was very helpful to me. And I needed to consider context and time periods more deeply. I seem to always go off of a modern cuff… so thanks for helping my perspective…

Hi Tabby, a lesson learnt for me, that for those from different disciplines, to offer more background! I this I got to wear the hat I wear most days, that of being an archaeologist. We all tend to forget that not everyone reading will come from the same academic discipline! I have a great love for wetlands and bogs, as my MSc was in bog palynology of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages near cult sites ( and KIlbeg bog here, with the creepy little red alder man, is very special to me!). So, glad I could offer context, and I would suggest, for wetlands, reading some of the really good papers cited here. It’s different from the Pleistocene animals, but we are the most deadly and complex Twilight Beast of them all! Kind regards,Rena, ‘Beasts.