In 1870 another species was wiped off the face of the Earth. The warrah, or the Falkland Islands wolf, was only known to science in 1792. Less than 100 years later it was gone. The last known induvial died in a zoo.

The first human settlement to the Falklands was in 1764, and has passed from French, to Spanish to British, to American control over the years. It was these early years that was the end of the only mammal on the Falklands. It’s scientific name, Dusicyon australis, literally means ‘the foolish dog of the south’. It was tame. It hadn’t seen humans before, so had no need to fear them. But this was disastrous. Sailors, and later settlers, would kill the warrah for meat and fur, and it wasn’t long before their numbers shrank.

Charles Darwin visited the Falklands in 1834, and as always, made detailed observations of this usual animal. It was constrained to the Falklands, found nowhere else in South America. He notes how people would kill them easily “by holding a piece of meat in one hand, and in the other a knife ready to stick them.” And he foresaw their extinction: “Their numbers have rapidly decreased; they are already banished from that half of the island which lies to the eastward of the neck of land between St Salvador Bay and Berkeley Sound. Within a very few years after these islands shall have become regularly settled, in all probability this fox will be classed with the dodo.”

We don’t know how the warrah arrived on the Falklands, which is 300 miles from the South American mainland. But we do know that its ancestor, Dusicyon avus lived in South America.

Dusicyon avus were widespread across South America and fossils have been found in Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Patagonia. Although called a wolf because of the Falkland Islands wolf, both species are actually closer to foxes than to wolves. DNA research into the fossils of D. avus showed it to be closely related to the odd, leggy, Manned Wolf (which again the name is misleading, as it is neither a wolf nor a fox!).

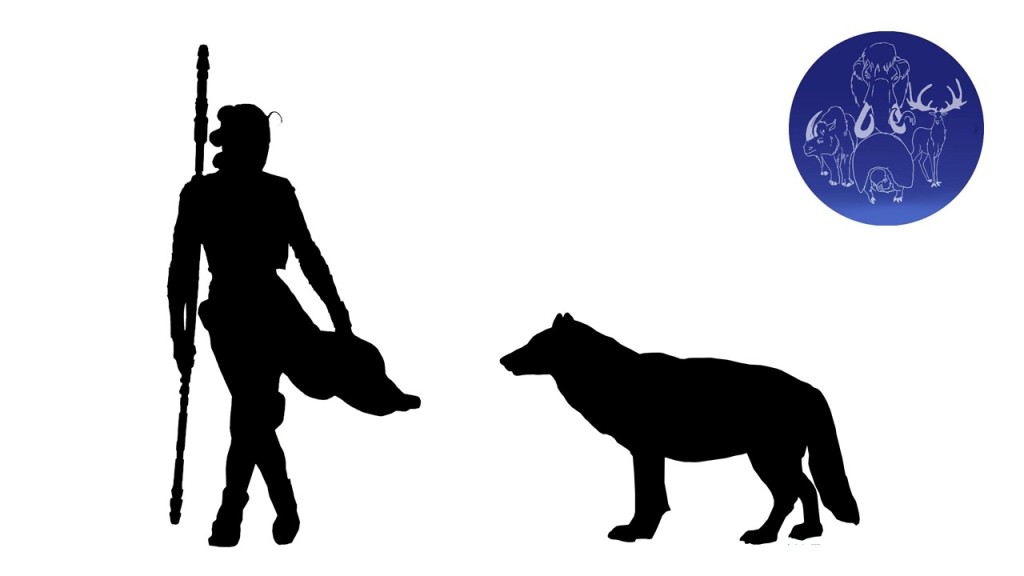

About the size of a small Alsatian, D. avus were very common in the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. We can find out a lot about how they would have lived by looking at their bones. Analysis of the skull shape suggests that they may have filled the same ecological niche as jackals do today. It was likely a scavenger, whilst hunting smaller prey. We don’t know if they shared a similar life to jackals, which live as monogamous pairs, or more like large family packs similar to wild dogs. With shorter legs than wild dogs, it is more likely they were not long-distance runners chasing prey down. But they were very successful, and ranged over most of grass plains of South America, which makes their extinction very strange.

It was thought that they became extinct around 3000 years ago, which is late in comparison to other extinctions in South America (between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago). Recent radiocarbon dating suggests they became extinct as recently as 400 years ago. This is extremely recent. And quite sudden. Some researchers have suggested that a more humid climate may have changed the available prey for D. avus, but these were more likely to be opportunistic predators, so it seems very unlikely. They lived in open grass environments, across varying climates, so a change in humidity wouldn’t have affected them much. Humans did have a relationship with these animals. Several burial sites contain bones of D. avus, with at least one potentially being intentionally buried: suggesting that it was a tamed animal (people have tamed wild foxes across the world for centuries). Their disappearance does coincide with Europeans settling in the Americas, and domestic dogs, and increased human presence could have just added that extra pressure.

This isn’t a well-known beast. Giant sloths and sabre tooth cats get a lot of the attention when it comes to Pleistocene animals from South America. But this little fox-wolf was a part of their ecosystem too. And they shouldn’t be forgotten. There are some who, like the thylacine, believe that D. avus is still out there. Sadly, I don’t think so. Sadly, these wonderful little animals are one in a long list which are gone from our beautiful planet forever.

Written by Jan Freedman (@JanFreedman)

Further reading:

Austin, J. J., et al. 2013. The origins of the enigmatic Falkland Islands wolf. Nature Communications. 4 (1552). [Full article]

Hamley, K M., et al. 2021. Evidence of prehistoric human activity in the Falkland Islands. Science Advances. 7 (44). [Full article]

Prates, L. 2015. Crossing the boundary between humans and animals: the extinct fox Dusicyon avus from hunter-gatherer mortuary context in Patagonia (Argentina). Antiquity. 88 (342). pp.1201-1212. [Abstract only]

Meloro, C., et al. 2017. Evolutionary ecomorphology of the Falkland Island wolf Dusicyon austalis. Mammal Review. [Abstract only]

Prevosti, F. J., and Martin, F. M. 2013. Paleoecology of the mammalian predator guild of Southern Patagonia during the latest Pleistocene: Ecomorphology, stable isotopes and taphonomy. Quaternary International. 305. pp.74-84. [Abstract only]

Prevosti, F. J., et al. 2015. Extinctions in near time: new radiocarbon dates point to a very recent disappearance of the South American fox, Dusicyon avus (Carnivora: Canidae). Journal of the Linnean Society. 116 (3). pp.704-720. [Full article]

Slater, G. J. 2009. Evolutionary history of the Falklands wolf. Current Biology. 19. pp.937–938. [Full article]

A fascinating article! Thank you 🙋♂️

Thank you Ashley! We’re really glad you enjoyed it! 🙂

What a beautiful animal.