When hiking high in the Alps you may encounter the devil himself. Or so claims Swiss naturalist and mountaineer Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), when he writes, that one will be only ‘in the company of the devil,…’ if climbing the Alpine peaks. De Saussure was indeed describing a horned animal with brown to black fur, but despite its appearance, the chamois is not really a demonic entity. The chamois is a gracile, small ungulate, native to many European mountains, with characteristic backwards hooked horns. Like real goats, chamois are excellent climbers. The flexible, cloven hooves are well adapted to move on rocky and rugged terrain. With a soft inner hoof-pad and a hard outer rim, the hooves will find grip even on the steepest cliffs. The name chamois derives from the Greek kemas, a name given in antiquity to wild goats. Kemas itself derives from kamp, an ancient Indian word for jumping. Seeing a chamois jump from rock to rock one can understand why this name fits it so well. However, some anatomical peculiarities separate this animal from real goats, for example, male chamois have no beard. The famous Gamsbart, the ‘chamois-beard’ displayed by hunters on their traditional hat, is made from a tuft of long hairs, growing on the back and rear end of male chamois during the rutting season. Early zoologists described the chamois as a European antelope species. However, today the chamois is classified as mountain-goat in an own genus, named Rupicapra.

The chamois plays an important role in Alpine folklore. In medieval times the Alps were often simply referred as Gamsgebirg, the chamois mountains, and still today many names of mountains or peaks refer to this animal. Some legends tell that the chamois was indeed created by the devil, to lure young hunters to their death in the mountains. Other times, so says a legend from the Italian Dolomites, the devil himself, disguised as a pitch-black chamois, appeared to the terrified hunters.

The hunt for chamois was indeed very dangerous. Hunters used ropes to catch the animals or long spears to push them from steep cliffs. Many stories tell about hunters who fell to their death. With the invention of rifles, the hunt became much easier and safer. Between 1700-1850 the species became rare in the Alps. De Saussure writes in 1780 ‘Though the profit is small, the people of Chamouni hunt … with passion, and so these creatures are diminishing in number in the most noticeable fashion. … The hunters of Chamouni have already utterly destroyed or driven away the bouquetins [ibex], which, once were common on their mountains, and it is likely that in less than a century neither chamois nor marmots will be seen.’ In the 19th century, the chamois was locally extinct, but fortunately, with the introduction of modern hunting rules and the creation of protected areas, nowadays the chamois is again common in the Alps.

Finnish vertebrate paleontologist Björn Kurtén (1924-1988) referred to the origin of the genus Rupicapra as a mystery. Today chamois populations are found in the European Alps, Apennines, Pyrenees, Carpathian Mountains and the French Massif Central (and introduced in New Zealand), even if it the genus is not considered of European origin. Fossils are indeed very rare and the chamois seems to appear suddenly in the fossil record during the last interglacial. Probably the ancestors of the three modern chamois species, the Alpine-Chamois R. rupicapra, the Pyrenean-Chamois R. pyrenaica and the Apenninic-Chamois R. (pyrenaica) ornata, migrated during the Riss glaciation (250,000-150,000 years ago) from Asia into Europe, becoming abundant here during the last ice age (80,000-12,000 years ago) and colonizing all mountain ranges in central Europe.

Living in mountains helps the chamois to evade most predators, with the exception of humans and eagles. The fossilization of bones is difficult in such a terrain because carcasses are exposed and scavenged. Fossils are therefore known only from bone accumulations in caves. As are fossils rare, so is the prehistoric art showing the chamois. Maybe this animal, living on inaccessible terrain, was a difficult and not very appreciated trophy for prehistoric hunters. There was just no interest to depict it. The rare examples we have are however quite intriguing. There are only six sites of cave art known to date, all located in France or Spain. One example is a single chamois, shown in a painting of red ochre in the Cave of La Pasiega, Spain.

Quite more common are depictions in prehistoric small, ‘mobile’ artwork. An entire chamois herd was found as engraving on a reindeer-bone. Discovered in the cave of Gourdan, France, the scene maybe shows a lion, spotted in the background, chasing the herd (modern chamois are still highly gregarious, forming large herds during the winter).

In one curious example found in the Mas d’Azil Cave, a young chamois (or maybe an ibex), carved into a spear-thrower made from horn, looks back at birds, picking on its own feces. Another mysterious discovery involves a small bone-disc with engravings on both sides, discovered in the archaeological site of Laugerie-Basse. Believed to be an early example of a bottom, its exact use is unknown. It was suggested that it was used as decoration on spindles, used for spinning yarns from natural fibers. One side shows a standing animal, on the other side, the animal seems to lie on the ground. If the disc is spun quickly enough, the chamois seems to repeatedly stand up and lie down. Maybe this is the oldest known example of an animation known to date, with an age of 12,000 years.

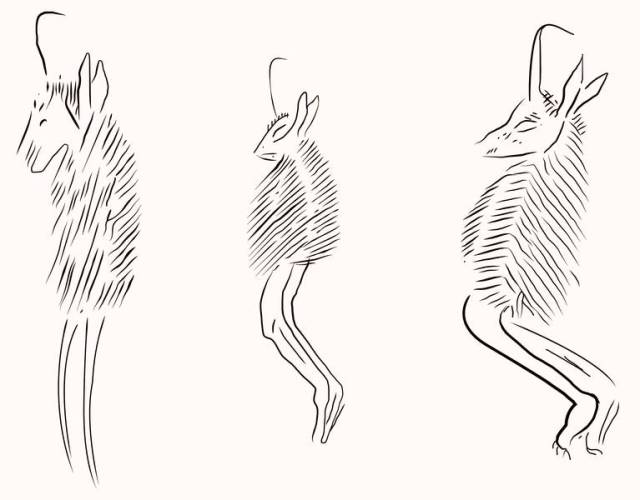

However, the most enigmatic depiction are the ‘chamois dancers’, found as an engraving on a mammoth tooth, discovered in the Abri Mège, Teyat in France. The three little chamois with human legs could be animal spirits or shamans, wearing the animal’s fur in some sort of ritual. It is also possible, that the engraving shows a hunting scene. Like some modern hunters, hunters 17,000 years ago could have approached a herd by disguising themselves as animals.

At the end of the last ice age, when the treeless mammoth steppe was slowly replaced with forests, the chamois, well adapted to cold environments, followed the receding glaciers into the mountains. There the various populations became isolated. The modern spotted distribution and the various recognized species are the results of this isolation and local evolution. However, this tough ice age survivor is nowadays threatened by tourism and climate change. In some areas, way too many tourists have pushed the chamois from its habitual pastures to less suited grounds. A resent study showed that as temperatures in the Alps continue to rise, the average body size of young chamois tend to shrink. It is not entirely clear if this is the direct result of chronic undernourishment, as high temperatures cause stress in the animals, they have to rest more and can dedicate less time searching for food. Diseases and parasites, like the feared mange, caused by parasitic mites, can spread better with warm temperatures.

Despite this, it is still quite easy to spot herds of chamois in the Alps. One should just be aware if encountering a pitch-black chamois. It could be a coal-chamois, as a rare variety of too intense pigmented chamois is called, maybe a shaman in a fur costume, or maybe it really is the devil in disguise…

Written by David Bressan (@David_Bressan)

Edited by Jan Freedman (@JanFreedman)

Further Reading:

KURTEN, B. (2007): Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Aldine De Gruyter Publisher: 317. [Abstract]

LOVARI, S. (1987): Evolutionary aspects of the biology of chamois, Rupicapra spp. (Bovidae, Caprinae). The Biology and Management of Capricornis and Related Mountain Antelopes: 51-61. [Abstract]

Interesting little tidbit about the ancient animation!