Reconstruction of a European Cave Bear (Ursus spelaeus) by Sergiodlarosa (Image from here)

Humans and bears have a strange relationship. On the one hand we see them as lovable, smart, curious creatures (think Baloo from the Jungle Book). On the other, we have taken great pains to exterminate them wherever and whenever we could. Thankfully, no bear species has gone extinct for over 10,000 years (although many subspecies have been lost). During the Pleistocene, the old world was home to a complex of species that may have been amongst the biggest of bears. The cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) was perhaps the first Twilight Beast to be studied in a scientific sense, thanks to the millions of bones the animal left behind in caves throughout Europe and Asia, the legacy of many individuals who failed to survive hibernation. Thought to have inspired legends of dragons that lived in caves, the bones were so numerous that they were occasionally mined as a source of phosphate. Named way back in the 18th century by Johann Christian Rosenmüller, the cave bear has been at the forefront of Pleistocene research ever since. This vanguard position continues into the present day: Ursus spelaeus was the first extinct mammal to have its nuclear genome sequenced. The oldest mitochondrial genome we have is that of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear (and it was used to test methods that were later utilised to sequence DNA from Homo heidelbergensis)

The cave bear (along with other “species” within the complex such as Ursus ingressus, Ursus deningeri) was a huge animal. Larger than the largest Kodiak brown bears (Ursus arctos), this imposing creature was probably a strict vegetarian rather than an omnivore. Analysis of teeth micro-abrasions and the stable isotopes that were incorporated into the bones show that these were gentle giants (although, giant herbivores are not to be underestimated, as anyone who lives around hippos or elephants will tell you). They may have been one of the main prey of another Pleistocene predator, the cave lion (Panthera spelaea). One can imagine a stealthy lion, winding through the winter caves, picking off the hibernating bears.

We still find traces of the lifestyle of the vanished cave bear within European caves. Many caves, including the famous Chauvet, still have visible marks from where the animal sharpened their claws on the walls. In some cases Palaeolithic people incorporated the marks into their art. Some caves (e.g. Große Klingerberg Höhle in Bavaria) have circular depressions visible in the cave floor, which have been interpreted as bear nests, caused by the animal turning in its sleep while hibernating. Speleologists have even recovered kidney stones from amongst the skeletons of cave bears.

Examples of cave bear trace fossils from the Ursilor cave in Romania. Top: footprints, Middle: clawmarks, Bottom: hibernation nests. Images ©Cajus Diedrich

Perhaps the most evocative sign left by the cave bear, which speaks of how integral the species once was to the European ecosystem, and how long it was a part of it, is something known as Bärenschliffe. Simply put, this is stone found in narrow cave routes that has been polished to a reflective shine by the scratching and rubbing of thousands of cave bears over tens of thousands of years.

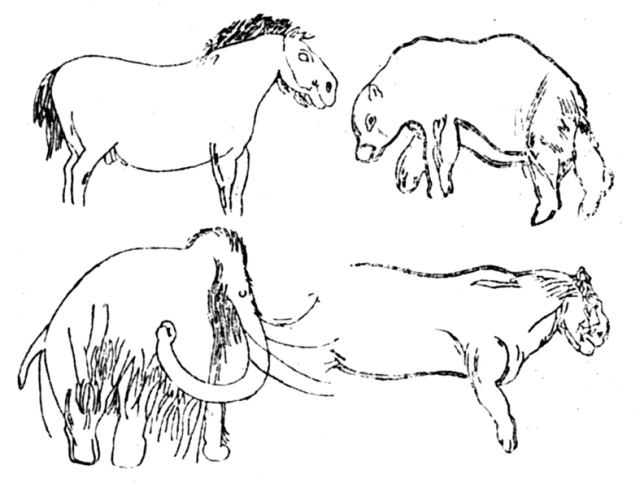

Within these caves, the bears would have occasionally encountered another apex predator (Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis). There are a few images within cave art that may be of the cave bear. Separating the paintings of brown bears and cave bears can be difficult but there are some morphological differences that can point us in the right direction. Compared to brown bears, cave bears have a huge protruding forehead, which is sometimes noticeable in cave art.

Top: The distinctive skull of Ursus spelaeus. Image by Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom: Public domain image of art from Les Combarelles cave, showing a bear (top right) with the distinctive forehead of Ursus spelaeus

The last cave bears probably died about 27000 calendar years ago, much earlier than the extinction of mammoth, woolly rhino, or cave lion. Genetic evidence suggests that this extinction occurred after a prolonged period of genetic bottlenecking. The cause is likely to have been a combination of change in climate affecting the nutritious vegetation the cave bear needed as well as an increase in pressure from Palaeolithic humans for cave sites.

Written by Ross Barnett (@DeepFriedDNA)

Further Reading:

Dabney, J., M. Knapp, I. Glocke, M. Gansauge, A. Weihmann, B. Nickel, C. Valdiosera, et al. “Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of a Middle Pleistocene Cave Bear Reconstructed from Ultrashort DNA Fragments.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2013). [Article]

Kurtén, B. The Cave Bear Story; Life and Death of a Vanished Animal. New York: Columbia University Press, 1976. [Book]

Noonan, J. P., M. Hofreiter, D. Smith, J. R. Priest, N. Rohland, G. Rabeder, J. Krause, et al. “Genomic Sequencing of Pleistocene Cave Bears.” Science 309 (2005): 597-600. [Article]

Peigne, S., C. Goillot, M. Germonpre, C. Blondel, O. Bignon, and G. Merceron. “Predormancy Omnivory in European Cave Bears Evidenced by a Dental Microwear Analysis of Ursus Spelaeus from Goyet, Belgium.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2009). [Article]

Rosendahl, W., and D. Döppes. “Trace Fossils from Bears in Caves of Germany and Austria.” Scientific Annals, School of Geology AUTH 98 (2006): 241-49. [Article] [This paper has excellent images of bärenschliffe]

Stiller, M., G. Baryshnikov, H. Bocherens, A. Grandal d’Anglade, B. Hilpert, S. Munzel, R. Pinhasi, et al. “Withering Away-25,000 Years of Genetic Decline Preceded Cave Bear Extinction.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 27, no. 5 (2010): 975-78. [Article]

Reblogged this on FromShanklin.

Pingback: Survivors | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Going underground | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Could you Bear to eat Pooh? | UCL Researchers in Museums